Interview to Alessandra Quarto

Director Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan

Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli was born in 1822 into an aristocratic, wealthy and intellectually lively family background: on the one hand, his father’s considerable wealth, on the other, the cultural humus of the Trivulzio family. How decisive was his mother Rosa Trivulzio, and the environment of artists and intellectuals she surrounded herself with, in Poldi Pezzoli’s education?

I would say fundamental! His mother, Rosa Trivulzio, the daughter of an intellectual protagonist of neoclassical and Enlightenment Milan, the Marquis Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, had grown up in a cultured environment, habitually frequented by men of letters such as Vincenzo Monti and Giuseppe Parini, who dedicated an ode to her marriage to Giuseppe Poldi Pezzoli in 1819. Marquis Trivulzio was also a refined collector of antique books and illuminated manuscripts, now the core of the Trivulziana Library in Milan, of rarities, ivories, gold, antiquities and precious objects worthy of a 17th-century Wunderkammer. Naturally, this stimulating environment made Rosa Trivulzio the absolute inspirer of Gian Giacomo’s collection, she who loved to surround herself with great talents such as Giuseppe Molteni, Massimo d’Azeglio and Giovanni Battista Gigola, one of the finest illuminators of the neoclassical era; Rosa became a patron of very famous artists, including Lorenzo Bartolini, who was at the time the most admired Italian sculptor after the death of Canova. Widowed very early, in 1833, she marked her son’s upbringing with beauty, culture and refinement as essential components of life, to the point that collecting for him would not only be a habit of lineage, but almost the very purpose of his life.

Gian Giacomo’s interests were initially directed towards arms and armour. This was not an unusual choice: in the course of the 19th century, the market and collecting of antique weapons experienced a huge boom throughout Europe. Between 1846 and 1848 he acquired several hundred weapons and armour; purchases continued throughout his life, with an ever-increasing focus on quality, so much so that by the third quarter of the century Gian Giacomo had become the most important collector in Italy in this field.

How much did frequent travels in Italy and abroad, international museums and collections, especially French ones, inspire Poldi Pezzoli’s house-museum project?

During the insurrection of the Five Days of 1848, Gian Giacomo financed and supported the anti-Austrian uprising and for this he was forced into exile for a year and paid a very large fine in order to return to Milan. The circumstance had a positive side, however: for over a year he travelled in Italy, to Switzerland and France, where he had been years before with his mother, and England, visiting galleries and various exhibitions. He was certainly particularly impressed by the new Musée des Thermes et de l’Hôtel de Cluny, created by Alexandre du Sommerard, a pioneer of romantic museography and author of a five-volume work that became the main European vehicle for disseminating knowledge of medieval applied arts. Inaugurated in 1843, the Hotel de Cluny had a collection consisting not only of paintings and statues, but also of precious antique furniture and objects of applied art, also chosen to evoke a refined domestic atmosphere.

The resounding success of this new interpretation of the past and the associated museographic model inspired the project of Gian Giacomo who, having returned from his travels, put the stimuli and suggestions he had received to good use, creating what in the 1850s became one of the most beautiful house museums in Europe, admired by great artists and connoisseurs, German and English travellers.

The Poldi Pezzoli house-museum has always been a model for European residences including the Jacquemart-André Museum opened in Paris in 1912, the Wallace Collection opened in London in 1900 and, finally, the Frick Collection in New York.

Moreover, thanks to his friendship with Giuseppe Molteni, a portrait painter, restorer and family friend, he came into contact with leading European art critics. Among them were the German Otto Mündler, the Italian Giovanni Morelli and the Englishman Charles Eastlake, director of the National Gallery in London, considered to be the most skilled and experienced connoisseurs of the 19th century, who directed him to auctions in Milan and debated attribution issues of his collection.

Moreover, as revealed in their respective notebooks and diaries, on their periodic trips to Milan in Italy and Europe, they did not miss any opportunity to visit private collections to ‘scout out’ antique paintings that could be ‘eligible’ for the National Gallery in London due to their high quality and impeccable state of preservation.

The house’s eclectic taste and diverse styles were distinctive of 19th century aesthetic trends. But for Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli, the house is not only the expression of a status or an artistic trend, but primarily of a thought that underlies the function of art, given Poldi Pezzoli’s decision to set up a Foundation. What is the common thread that unites everything?

Hand in hand with the collection, Gian Giacomo was responsible for the decoration of his flat, entrusted to the most acclaimed artist-decorators of the time including: Giuseppe Bertini, Luigi Scrosati and Giuseppe Speluzzi. The result was a sequence of rooms inspired by different styles of the past: the staircase and bedroom in the Baroque style, the antechamber in the French rocaille style, the Black Room in the Northern Renaissance style, and the Study Cabinet in the Italian 14th century style. Eclecticism, the revival of styles and artistic techniques of the past, was the fashionable trend at the time, so much so that the rooms of his house became precious ‘containers’ for old paintings, sculptures, furniture and applied arts.

The decision to establish an artistic foundation ‘for public use and benefit in perpetuity’ certainly came from the aspirations underlying 19th century collecting, steeped in idealism, which preached the education of humanity through art. Gian Giacomo was a patron and intended to entrust his collections with an educational mission for everyone, not only students and artists, but also for ordinary people. This is the vision that the museum’s management pursues today: to open up the museum to new and different audiences and to bring all people closer to art by offering tools that allow visitors to enter into dialogue with the extraordinary collections, promoting the museum as a tool for the cultural growth of the city.

The layout of the house blends original furniture purchased on the antiques market with works by artists and decorators from the mid 19th century, all under the coordination of Giuseppe Bertini. How much did these artistic enterprises contribute to the promotion of Italian high craftsmanship of the time?

Certainly a great deal. Let us not forget that the young painter and glassworker Giuseppe Bertini had achieved considerable success in the first universal exhibition organised in London in 1851 (the event where Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace was designed and built) by exhibiting a Dantean stained-glass window that he later replicated for Dante’s Studiolo, a triumph of medieval arts that combined Romanesque, Moorish and Gothic suggestions. Bertini and Scrosati had created a true work of goldsmithing, a treasure chest destined to promote Milanese craftsmanship throughout Europe.

In this way, Gian Giacomo supported and safeguarded the city’s artistic craftsmanship for more than two decades. From the 1950s, in fact, the house became the site where contemporary Milanese decorative arts became a model of excellence in Europe, distinguished by the careful and profound study based on the observation of past techniques, through the works with which the flat was progressively enriched.

Not only that, with the opening of the house-museum in 1881, it was stipulated that tickets were to be free for ‘artisans engaged in related industries’ in order to protect and develop the minor arts that he himself had promoted with great fervour. In the museum’s opening speech, Count Francesco Sebregondi – secretary of the Brera Academy – emphasised the function of ‘helping the working class to educate themselves’. The project of the art foundation also aimed to support contemporary artists who, by visiting the museum, would be able to admire the masterpieces of the past and draw inspiration for their own works.

The museum still has a strong connection to craftsmanship and design and, in fact, during Design Week it hosts exhibitions celebrating the dialogue between iconic products of major companies and the museum’s applied arts collection.

What was the contribution of scholars and art critics to the constitution of its collections, and who were the leading figures, also in the artistic debate around the attribution of works?

Gian Giacomo bought from a dozen or so antiquarians and had an entourage of illustrious experts around him: Giuseppe Baslini, one of the most renowned antiquarians in Milan, Giuseppe Bertini, director of the Brera Art Gallery, Giuseppe Molteni, Trivulzio house portrait restorer and consultant to institutions such as the Louvre and the British Museum. The armourer and antiquarian Carlo Maria Colombo was joined by the Scala stage designer Alessandro Sanquirico. It was probably the latter who suggested that he create a Gothic-style set design for the Armoury, which was entrusted to one of Sanquirico’s pupils, Filippo Peroni, who was a set designer at La Scala.

Initially it was Giuseppe Molteni who put Gian Giacomo in contact with the academic and connoisseur-collector circles. Between 1853 and 1855, Bernardino Biondelli, director of the Numismatic Cabinet in Milan, was his consultant for archaeological and medieval purchases. And again, the critic Giovanni Morelli, with whom he was in contact from 1861, who was a very influential personality on the Italian and European scene between the 19th and 20th century thanks to his attribution method based on the observation of so-called particular signs. It was he who supported Gian Giacomo’s choices for the establishment of the Italian collection. Let us not forget that the development of private collecting and connoisseurship, the delocalisation of the antiques market, the blossoming of the figure of the travelling agent, attributive reconnaissances and the work of great scholars including Giovanni Morelli himself, are phenomena that characterised the formation of Gian Giacomo’s collection.

What opportunities did the antiquarian market in the second half of the 19th century present to those with taste and financial means?

To range over every sector, from painting to porcelain, from glass to sculpture, from jewellery to furniture, from watches to textiles, with that encyclopaedic spirit that characterised 19th century collecting. Moreover, it should not be forgotten that the climate was one of great cultural ferment, fuelled by Universal Expositions and the flow on the antiques market of works of art from the dispersal of ancient princely collections and the suppression of churches and convents, which made an enormous quantity of sculptures, paintings and furnishings available to collectors. In fact, favourable socio-political circumstances combined with legislative provisions – the abolition in 1865 of the bond of fedecommissum, which obliged to maintain the unity of the family collection, and the absence until 1902 of unitary laws for the protection of cultural assets – created a fortunate season of art trade and collecting, attracting collectors of the highest level.

Economically, Europe was going through a period of strong growth, but also of great market volatility. Italy was lagging behind in many respects, and the unification process was turbulent and fiscally costly. Gian Giacomo experienced exile and had his property confiscated by the Austrians. It is natural to think that his collecting was in some way influenced by this scenario.

Selling, buying, collecting: timeless actions, actions that are repeated throughout human history, actions to which we owe the formation and, thanks to it, the preservation of immense heritages of works of art and artefacts from the past.

The museum-house is a true testament to the love of the beautiful, the extravagant and the mysterious: tales of epochs, of fashions, of different sensibilities that in the end are narratives of our roots, and as such indispensable for understanding where we want to go, and how we want to live our present.

Of the museum’s collections, which are the most representative and which are the most valuable works it holds?

Gian Giacomo composed the antique picture collection between 1853 and 1879. The ‘nationalistic’ spirit fuelling the gentleman’s ambitions should therefore come as no surprise.

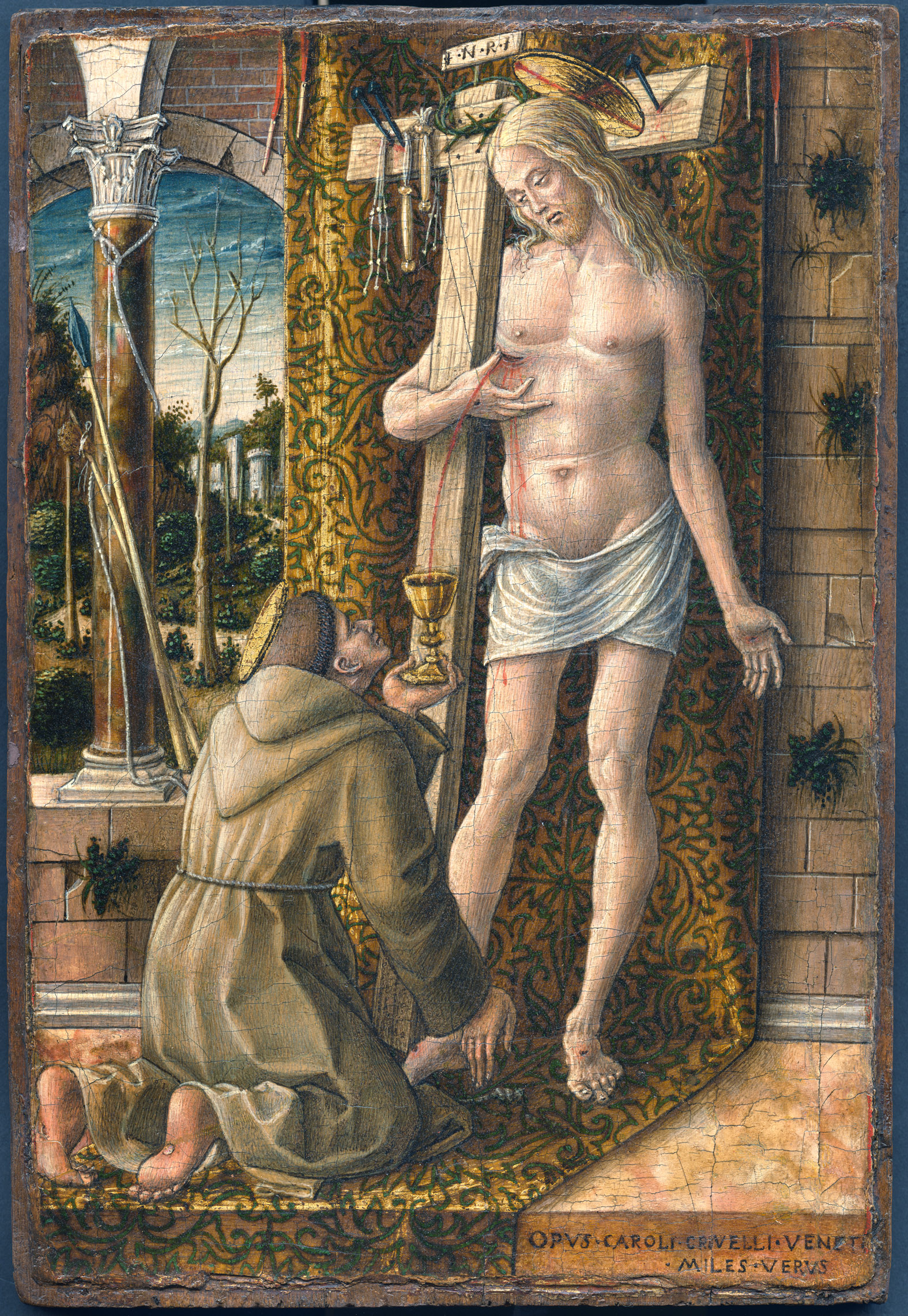

The collection boasted exceptionally high quality pieces by the most famous Renaissance masters, such as Botticelli, Mantegna, Cosmè Tura, Carlo Crivelli, Giovanni Bellini, Piero del Pollaiolo, as well as later works by Canaletto and Guardi, and medieval paintings with gold backgrounds by Vitale da Bologna and Pietro Lorenzetti. The works, almost always of medium size because they were intended for private collecting, in good condition and often signed, were in line with the taste of the emerging art critics.

Today, the collection comprises more than 6000 objects including paintings, sculptures, ceramics, glass, weapons, gold, watches and textiles. For each collection, the museum holds extraordinary masterpieces, considered by critical literature to be the most important in the world.

Obviously, these include the nucleus of Italian and Lombardy Renaissance paintings, the armour belonging to the Gonzaga, Borromeo and Savoy families. Among the porcelain, the tea and coffee service made by the Meissen manufactures for the Borromeo family. Also, Lorenzo Bartolini’s extraordinary work, Trust in God, a life-size white marble sculpture commissioned by Rosa Trivulzio from the Florentine sculptor in 1833, following the death of her husband. And again, among the textile collection: the Tiger Carpet (woven in Quazvin, one of the royal cities of central Persia, between 1560 and 1570) and the Hunting Carpet (a marvellous specimen from north-west Persia, dating from the first half of the 16th century). It is important to mention from the watchmaking collection the Chariot of Diana, a princely wunderkammer automaton still in working order.

The Poldi Pezzoli is a museum open to purchases and donations. Since Gian Giacomo’s death, what have been the most important acquisitions, past and recent?

Gian Giacomo had not only consigned the results of his acquisitions to posterity during his lifetime, but had also provided for the management and growth of the museum’s collections by disposing of a substantial annual sum that Bertini – the museum’s first director – used to buy new works. Since the Second World War, the museum has received thousands of objects, including entire collections such as Bruno Falk’s mechanical watches, Piero Portaluppi’s sundials and Luigi Delle Piane’s pocket watches, including the magnificent French Jacques Goullons watch decorated with an enamel by Jacques Vaquier, which reproduces Raphael’s Battle of Constantine in miniature.

Today, the Museum is the most important Italian institution in the field of artistic watchmaking from the 16th to the 19th century.

Also, Coptic textiles and lace. Of great interest is the bequest of eighty European porcelains from the 18th century donated by the Zerilli Marimò family, with very rare objects from the early years of the Meissen manufactory. And before that, Ginori’s Laooconte.

Particularly rich was the testamentary legacy of Margherita Visconti Venosta, who left the museum works such as the tondo by Pinturicchio, a Madonna and Child by Bergognone, and the Croce astile attributed to Raphael.

The museum’s recent history continues to be rich in bequests and donations, including Giovanni Battista Moroni’s Il cavaliere in nero (The Knight in Black) in 2004, and the Vergine leggente (The Reading Virgin) attributed to Antonello da Messina in 2018. The museum receives many generous donations from the families of its city, which were recently celebrated in an exhibition dedicated to its donors: The Art of Giving. From Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli to Today (November 2022 – February 2023).

The figure of Poldi Pezzoli is profoundly linked to the Milanese fabric, both through his maternal ancestry, his political commitment to the Risorgimento cause and the uprisings of 1848, and his testamentary legacy to the house-museum. How significant is the figure of Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli for Milan then and now?

Upon his death, the Foundation was endowed with a life annuity of 8,000 lire a year, destined to cover running costs and the purchase of works of art ‘both ancient and modern’. This is an important message, perhaps one of the keys to the collection. Gian Giacomo was able to look as much at his present as at the past. The museum should have continued to grow in the same spirit that had brought the present and the past into dialogue with each other – not only through painting – for mutual benefit.

The museum’s life and mission are linked to the public, its presence and its generosity: all the generous collectors, private and public supporters who never abandoned Gian Giacomo’s project and made it their own, embracing its ethical and civic message, belong to the museum’s history.

Gratitude is very important and people from Milan feel a strong urge to give back.