Interview with Vincenzo Trione

President of Fondazione Scuola Beni Attività Culturali

Integration, connection and comparison are the three distinctive values of the Fondazione Scuola dei beni e delle attività culturali, an international institute founded in 2014 and funded by the Ministry of Culture, for training, research and advanced studies. What results have been achieved in recent years, and how is it possible to implement these values?

The first significant issue is the originality in the Italian scenario of the Fondazione Scuola dei beni e delle attività culturali, which started a few years ago having the French Heritage School as an important reference model, but with the need to design a unique identity in the panorama not only in Italy. This was not an easy task to achieve, because it was halfway between the space of post-university education, the world of work, and the system of cultural institutions in our country.

This is why we started from an idea that is quite important for the contemporary world – one of today’s great challenges – underlying the School’s philosophy: the need to move away from a vertical and very twentieth-century vision of the disciplines, in favour of a strictly horizontal vision, essentially committed to certain fundamental values: of connection, relationship, dialogue, but above all of transversality. I believe that it is precisely this concept of transversality, that is, the need to develop a broad, diversified multidisciplinary vision that is very attentive to contemporary needs, that is the key around which the School has worked in recent years.

The results achieved since I and Director Alessandra Vittorini took office in 2020 are many, relevant, and on different fronts. Among these is the public competition course, which has been awaited for many years, that the National School of Administration has announced for state managers in archives, libraries, superintendencies of archaeology, museums, fine arts and landscape, managed for the first time by the School, and which will shortly breathe life into the top management of the Ministry of Culture: a truly outstanding achievement that, as often happens in our country, does not make the headlines.

Alongside this institutional task – the School, by virtue of its genesis, obviously has a close and privileged relationship with the Ministry of Culture – there are other fronts on which we are moving, which respond to the need to explore new areas and new sectors of culture. Out of this need came the Toolkit for museum training programme, promoted by the School in collaboration with the International Council of Museums Italy, aimed at museum professionals, with the function of exploring new fundamental strategic areas not fully covered by operators in the sector, but for which the national public and private museum system feels the need. A project that sees the fundamental involvement of museum institutions: from the Uffizi Galleries in Florence to the National Galleries of Ancient Art in Rome, from the Egyptian Museum to the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, and even the Reggia di Caserta, where the training activities take place.

Another important project in which we are involved is the one with Intesa Sanpaolo, for the management of the artistic and cultural heritage and corporate collections.

Our idea is therefore to act as a trait d’union, i.e. to initiate a dialogue both with the public – meaning the Ministry, museums, but also the very wide network of the local administration system – and with the private sector, with which we maintain a secular relationship of great cooperation.

Italy has a millenary heritage yet to be exploited and communicated, which belongs to us and with which the world identifies us. How can we be innovative?

For about ten years in Italy, like Guelphs and Ghibellines, we have been arguing about our artistic heritage between those who support preservation and protection and those who support enhancement. Frankly, I think it is a tired war, one that absolutely must be overcome, because it makes no sense to pit these two sides against each other, which are the sides of a single discourse.

Italy certainly needs first of all to protect its heritage, which is not only that of the historic cities that we have been talking about for many years. Italy also has a very rich and ramified fabric where, unfortunately, peripheral realities are often in a dramatic and forgotten condition, despite having extraordinary potential.

The other sensitive issue is the narration of this heritage, a narration that clearly falls under the somewhat abused category of storytelling, which should proceed along two main lines. The first, based on the relationship with communities: it is no longer conceivable to have a heritage that is basically designed to communicate to tourists and not to the citizens of the area. A great challenge is therefore to ensure that museum sites, archaeological sites, are perceived as necessary steps for those who live within a given reality. The second direction is to use in a sensible and competent way all the digital devices that allow us to establish a link, in my opinion decisive, between off-line and on-line, that is, between the physical world, the world of collections and heritage, and the opportunities offered by technological devices, by the different platforms, to allow a more widespread and highly democratic knowledge of what we preserve.

In recent years, the Ministry of Culture has moved to fix some of the backwardnesses of our cultural heritage system, and to redevelop sites and places of our first-rate heritage. But there are, as you observed, peripheral realities that are experiencing dramatic conditions. Can we save this abandoned heritage also by involving the private sector?

I think that the relationship with the private sector is one of the ways forward, also for the management of widespread heritage. The example of autonomous museums is certainly indicative, but we must not forget that these are often great attractions: from the Uffizi to the Colosseum, from Brera to Pompeii. We need to work towards new systems of rules that make public-private partnerships sustainable, also from an economic point of view, in smaller sites, in those that are less accessible or have few visitors. This is an opportunity. Perhaps, a necessity.

The other side of the forgotten heritage is that of historic cities, which instead experience the problem of being crushed and distorted by tourism. How can these cities regain their identity, the reason why they have always been destinations for international tourism?

It is hard work, and more necessary than ever, if we think of cases such as those of Venice, Rome and Florence. In local development models based on cultural resources, it is necessary to look into the future, with long-term projects that set goals for the growth of communities and the development of tourism businesses. This is why, I say this as the president of a school, we need to create the right skills to make city administrators understand that culture generates economic and social effects even without chasing the ‘hit and run’ tourist. This is a long and arduous task, but it is what we are trying to do with a number of projects: I cite, for example, the Cantiere Città project, which works with the ten finalist cities for the title of Italian Capital of Culture, laying the foundations for greater awareness among civil servants and public managers.

The School’s areas of activity are in the fields of training, research, innovation and experimentation, the internalisation of Italian cultural institutions, and dissemination and editorial production. How does one train a cultural professional?

These areas are closely interconnected, but we would be making a mistake if we thought we were training a professional who combined all these skills. That is not the aim of the School.

Rather, we start from an important observation, namely, many of the professions that will emerge in the world of cultural heritage are still unknown today. I believe there is still a mismatch between the world of public institutions that regulate and design training and work systems, and the real world: there is a system of rules that tells professions by static categories, such as art historian, archivist, librarian, architect; and there is a real world, which asks for different skills capable of connecting these traditional knowledge to more current knowledge, related to marketing, management, communication, valorisation, social.

Tollkit for museum, a project of which I am very proud, is linked to professions such as the registrar, the conservator, the communicator, the expert in educational workshops. These are skills that museums and the world of cultural heritage urgently need, but towards which public institutions are often inattentive. Our aim is to offer the national museum system as a whole new professionals, and at the same time to intuit what will be the professions of tomorrow, in the knowledge that different disciplines need to be networked. This is the only possible way, because in a world where professions are changing rapidly, we cannot anchor ourselves to categories that belong to a distant past. The School wants to be the bearer of cultural values that go in this direction, that is, to dialogue, to connect, to relate what we considered distant until a few years ago. A mission that I believe is important.

Does this mean that the state is ready to institutionalise new professions?

I believe it is absolutely possible. The universities are beginning to move in this direction, and this is far from irrelevant. It is a goal that we cannot put off any longer. There will still be the vastness of a distant world that must be looked at with absolute respect, but I believe that this state of affairs is no longer thinkable. It is an urgency shared by traditional museums, archaeological sites, contemporary art museums, foundations, as common needs. The question is simple: universities and higher education institutions like our School have no choice but to be in tune with these urgencies, otherwise there is no chance. This is why I looked with great interest at the reaction of the participants to the call for PhDs in heritage sciences, the only one awarded with PNRR funds, which had a very high turnout in our country, with 200 scholarships available and 200 scholarships awarded, all of which attempt to address heritage issues in an innovative field. This denotes a significant focus on these new professions. This is the extra step that the School wants to take, making the institutions aware of a change of scenario that is already underway.

New recruitments also mean an economic investment on the part of the state, and this announcement comes after a very long time. How much margin do these new professions have in private institutions?

The private sector is an area of great importance and interest, which – by its very nature – is more responsive to the absorption of innovative professionals. The point here is to create the conditions in which this demand for work can be expanded and, therefore, in which private initiative in the cultural heritage sector can be fostered. On 4 May next, we will discuss these issues in an event dedicated to participation in the management of culture, which we will hold in our premises at the National Library in Rome.

Looking at the present, between public institutions and private foundations, do you see any significant enhancement projects?

The School has a very close relationship with foundations, such as with the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, which is actively involved in the Tollkit for museum project. But a clear distinction must be made between public and private institutions. Fondazione Prada does an extraordinary job, but it is a private institution that has to fill an institutional void, which is the lack of a contemporary art museum in Milan.

If I had to cite a model, I would tend to choose the Boijmans Museum in Rotterdam, which preserves a vast artistic heritage, from medieval European art to modern art. I find it an example of great interest that I have repeatedly mentioned as a destination to look at.

The Boijmans has initiated an extraordinary project of a new museum site to be built in order to enhance all the heritage still kept in the repositories – today one of the cornerstones of this new government is precisely to enhance the repositories. It has also made it possible for the first time to access the entire back office of the museum, such as the restoration laboratories, or the conservation laboratories, and to follow the activities remotely through digital devices and platforms. This, I believe, is a model to strive towards, aimed at enhancing the collections, the heritage, and also at making the best and most correct use of the devices and possibilities offered by digital.

In 1923, avant-gardes such as Cubism, Futurism, Fouvism, Metaphysics and the Dada Movement were already historicised. A century later, what is the landscape of contemporary art?

I look with great distrust at those who condemn the art of our time. In order to understand a century, we cannot judge it in the moment it happens. If we look at the 20th century, the 20th century avant-gardes – a subject I have studied in great depth – they represented a unique moment in the search for new languages of modernity. But each century said in its first twenty years all that it would develop in the next eighty, basically an afterword to what has been premised.

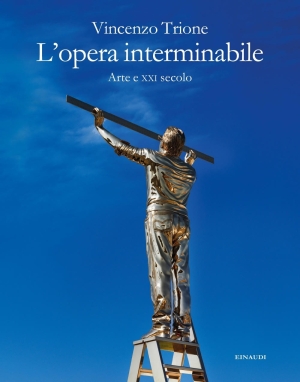

I am profoundly convinced that these first twenty years of ours have been a time rich in stimuli, rich also in rethinking artistic genres. I do not like to quote myself, but in 2019 I published a book for Einaudi that I hold dear, entitled: L’opera interminabile. Arte e XXI secolo dedicated to the great works created in the world since the beginning of this century, with artists who have radically challenged every boundary between languages.

Goodbye painting, goodbye sculpture, goodbye architecture and literature. My invitation is to try to construct works in which these languages somehow converge and lose their specificity. This, I believe, is the great legacy of art in the first twenty years of this century.