Interview with Roberta D’Adda

Curator of Fondazione Brescia Musei

The core of Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo stems from the art collections that Count Tosio left in bequest to the Municipality of Brescia in 1832. Who was Paolo Tosio, and what was the climate among the artists and intellectuals who frequented his home in those early decades of the 19th century?

Paolo Tosio was a cultured aristocrat who was lucky enough to dedicate his life to art. Born in 1775 in Sorbara, in the Brescian countryside, he never exercised any role in public administration other than those strictly related to the cultural dimension. He was therefore on the council that administered the Queriniana Library, was a member of the Deputation to the Fabbrica del Duomo, of the Commission for the archaeological excavations of the Capitolium and in that of the Monumental Cemetery.

The decision to collect came after an exciting stay in Rome, a stop along with Florence and Naples on the artistic journey he made between 1807 and 1808 with his wife Paola Bergonzi. He only went there once, but that was enough to make him fall in love with ancient art and Raphael, but also with contemporary art, because it was in Rome that he got to know and frequent the circle of artists who were most avant-garde at the time. His guide was the Brescian painter Luigi Basiletti, who spent several years in the papal city in contact with the most modern artistic circles, starting with those that gravitated around Antonio Canova and ending with the circles that brought together the French, German and English artists who were then staying in Rome. It was an extremely buzzing world, the one in which Italian Neoclassicism was born, and where, moreover, the first stirrings of Romanticism were also born, or at any rate of an approach to themes that went beyond those of the classical tradition, for example the love of Dante, whom Tosio met in Rome in the very circles where the Commedia began to be read and whom he brought to Brescia.

This cosmopolitan world of artists and intellectuals is the one Tosio tried to recreate in Brescia in his salon, where he held a popular conversation and which was open to all the guests who even then passed through the city, very often attracted by his collection – as it grew, so did its fame. At his side was his wife, a cultured woman who spoke several languages fluently, who corresponded with poets and artists, and who assisted him in the creation and management of his collection. The house was a destination for all art lovers passing through Brescia, and from Tosio’s epistolary we know that English, French and German artists came there from Europe. What attracted them were partly the masterpieces in the collection that still capture our attention, starting with Raphael, but partly, if not mainly, the works of contemporary artists that Tosio collected.

What examples inspired the collections at Palazzo Tosio?

The most significant moment from the point of view of displaying the collections is the commission that Tosio entrusts to Rodolfo Vantini, whom he asked to redesign a wing of the palace’s piano nobile that was basically designed to be a museum. We understand this mainly from the way it was conceived, with two parallel rows of rooms and lavatories and no functional home-like space designed to house the works. In one of the rooms, the four overlapping lunettes even form a kind of museum programme, a metaphor for the state’s duties to its citizens, which are to ensure health, exercise and nourishment of the body as well as the spirit, through the arts, music, literature, theatre and, of course, painting and sculpture.

The whole house is built as a sort of total work of art, in which the decorations dialogue with the works, creating real red threads that allow the entire collection to run around certain fundamental themes. From a formal point of view, this sequence of Vantini’s rooms is very interesting, both because the architect seeks a continuous variation in forms – the oval room, the octagonal room, the gallery – precisely by drawing inspiration from the residences of English collectors of which Vantini, being very curious and almost an exoticist, was aware; and because of the absence of windows, following the example of the rooms in the Pinacoteca di Brera. In particular from Brera comes all the attention to the theme of lighting, obtained through skylights in the ceiling that gave a diffused zenithal light particularly suitable for displaying works of art.

Today, the house is no longer as it was, but a major restoration and refurbishment programme promoted by the Ateneo di Scienze Lettere e Arti di Brescia is currently underway, which will allow the part reserved for 19th-century works of art to be reinterpreted almost in its original configuration, because the collection of ancient art – which was, moreover, displayed according to a very different criterion, with works placed close to each other and on several orders – is largely housed in the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo.

What taste did the Tosio collection of ancient paintings, which included the significant presence of Raphael, reflect? And what was its impact on the city and cultural circles of the early 19th century?

Tosio’s taste was oriented towards classicism, especially for ancient art. He was very interested in the artists of the Renaissance, of that particular moment of the Renaissance that was already mature but preceded Raphael’s Stanze. A sort of golden age before the beginning of what was then considered the corruption of Mannerism, a time when it was believed, again according to readings Tosio knew well, that artists still expressed their own direct sensitivity, especially in works of art with sacred subjects. In fact, Tosio was particularly sensitive to this subject, because he was personally moved by a sincere faith, favouring works of a religious nature intended for private devotion, mostly of small format with few figures in a meditative atmosphere. This golden age was flanked by other moments in which the reference to classical culture, and then to that of Raphael read as heir to classicism, had proved more successful, more accomplished, thus above all the 17th century in Emilia. In the same way, he preferred works of classicist or at least academic language among his contemporaries, but he was very open with respect to the choice of subjects, which he often left to the artists’ free will.

On the other hand, the presence of Brescian painters in his collection of ancient art was very few, mostly coincidental, for example a Romanino that he believed to be a Titian. The only Brescian artist recognised as such was Moretto, for it was precisely in the environment linked to Tosio and Vantini that the cult of Moretto as a ‘Brescian Raphael’ began to be nurtured, and thus as an artist capable of embodying in his work those ideals of harmony, composure and gentleness that Tosio sought precisely in Renaissance painting.

Clearly the presence of Raphael gave great significance to the collection. Tosio bought three works on the market with reference to the Urbino, two of which were accompanied by a certificate of authenticity, and these are the two that we still recognise as Raphael: the Redeemer and the Angel. The attribution of the Angel, however, was very soon called into question until it was completely lost, only to return in the early 20th century. The Redeemer, on the other hand, is a work that achieves great fame, due to the will of Tosio himself who promotes its engraved reproduction, to the point that it appears in the 1829 Italian edition of the Life of Raphael by Quatremère de Quincy, also edited by a Brescian, Francesco Longhena. The resonance of the work therefore gives the collection great visibility.

Although Brescian taste had already been oriented towards classicism since the 18th century, what Tosio brings of importance is a cosmopolitan vision, a vision updated on trends that are no longer local or Emilian, as was the case in the 18th century, but updated on a European taste.

His collection of contemporary art was particularly renowned, the first to become public in Italy in 1851, reflecting, as we have seen, a taste oriented between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. Which artists did the collection include?

The collection mostly comprised artists Tosio was able to come into direct contact with, i.e. living artists he wanted to frequent and enjoyed relations with; after all, he was not so much interested in buying a finished work as in being actively involved. In this sense, for example, the relationships established with Francesco Hayez, Giuseppe Diotti and Luigi Ferrari, the author of the colossal Laocoon that closes the exhibition itinerary of the current Pinacoteca, are wonderful. But Tosio also sought out artists with whom he could not establish this contact, such as Andrea Appiani, whom he recognised as an absolute master, probably influenced by the personal cult he had for Napoleon – of whom Appiani was the first painter – seen as the hero of modern Europe and, in part, the liberator of Italy in a season he had experienced as a young man. Moreover, Tosio was a man who was not afraid to get close to important figures such as Canova and Thorvaldsen, both of whom he reached through the mediation of Luigi Basiletti. Pelagio Palagi was also another key figure in his collection, from whom he commissioned Newton’s The Discovery of the Refraction of Light. There were also many paintings of genres that today we would consider minor such as landscapes or interior views, by artists who in those years were exhibiting at the Brera Academy, which Tosio frequented regularly.

Hence important commissions and an open-mindedness that went beyond regional circles, academy preferences, and led him to be somewhat unprejudiced in his choice of subjects. In this sense, Diotti’s Count Ugolino in the Tower and Hayez’s The Refugees of Parga are works that deal with very particular themes: Count Ugolino is a subject that in time became famous, but at the time was not yet popular, generating rather horror and revulsion for its macabre story; while I profughi di Parga is one of the works that opened the Romantic season in Italy, at least for the choice of theme: an episode of contemporary history that took place in 1817 that we would today define as highly topical. Tosio would also have liked a work depicting Psyche for his house, but neither Canova nor Hayez, for different reasons, succeeded in obtaining the commission: the former because a full-length sculpture was demanding and there were numerous works he already had to attend to; the latter because he did not like the theme which he considered too classical. Nevertheless, these two failed commissions brought two masterpieces to his collection, the bust of Eleonora d’Este and The Refugees of Parga.

Having become public property through a bequest in his will, after a few years, in 1851, the Tosio collection, now the Municipal Art Gallery of Brescia, opened to the public, and was soon enriched with numerous other collections. What were the criteria adopted in the selection of the works brought into the Art Gallery, and what programme did these new acquisitions respond to?

When the Pinacoteca opened, it became the city’s point of reference for painting, and if on the one hand small or medium-sized donations from other collectors began to be made and finally found a destination here, it also became the place where works that the city had previously begun to collect, at least since the Napoleonic suppressions, were channelled. The most important ones had been exhibited in the Palazzo della Loggia and the Queriniana Library, but large deposits of material had been created. It must also be said that Brescia at the time boasted an important school of extractors, i.e. restorers specialised in tearing down frescoes, and as the city modernised and proceeded with the demolition of historic buildings, all the pictorial hangings began to flow towards the Art Gallery.

These heterogeneous materials arriving at Palazzo Tosio created a difficult situation, which was perceived as such by the connoisseurs themselves at the time, especially those who were personally linked to Tosio’s memory, and who saw this sort of total work of art that was his Gallery – which we must imagine was truly a jewel of balance and perfection – being disrupted by the progressive arrivals that sometimes involved the presence of works of great dimensions, or stylistically distant from those that made up the original collection.

At that time there was no real policy of acquisitions in the modern sense of the term, but the double register that characterises the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo even today began to manifest itself, i.e., on the one hand the works of collectors’ provenance which were mostly non-Brescian paintings, since a strong idea of the Brescian school had not yet been born – except for a few rare exceptions, which in any case do not flow into the Art Gallery – and those who could collect, also for reasons of status as well as passion, were oriented towards other artistic contexts; on the other hand, this conspicuous, and we must imagine also bulky, part of works from the territory, which had nothing to do with the collecting part. This gave rise to a situation that we must imagine was unmanageable, also for reasons of space, so that the desire to differentiate soon arose, which led Brescia for a brief period at the end of the 19th century to even have two picture galleries.

What were the opportunities that led to the creation of the Pinacoteca Martinengo in 1889?

The city began looking for a home for Brescian art very early on, because these two souls of the collection were perceived as not being compatible with each other. Several unsuccessful attempts were made, until Count Francesco Leopardo Martinengo da Barco decided to leave his aristocratic palace – the current sole seat of the Art Gallery – to the city, which came to be completely empty except for a single painting by Angelica Kauffmann, with the library and the collection of musical instruments and medals attached. Having seized the opportunity, the City Council decided to adapt the building as a museum venue and undertook some work on the architectural front, including the renovation of the façade, the creation of an entrance hall and a square in front of the museum, where modest civic buildings had previously stood.

The idea of a civic museum that is an expression of Brescian painting, which grew in prestige during the 19th century due to the contribution made by European scholars and connaisseurs, and which had its ambassadors in Romanino and Moretto, has its place in the new Pinacoteca. How is the collection structured?

It is a collection that from the very beginning – following the path traced by Tosio – also included contemporaries, so much so that today we conserve conspicuous groups of second-century Brescian art. A picture gallery that progressively saw different strands gain weight. The initial phase – which had already begun with Palazzo Tosio – focused on the great masters Romanino and Moretto, and the altarpieces of churches that had been suppressed or were still in use, from which the most important masterpieces were taken, sometimes to ensure their preservation and sometimes with the declared aim of enriching the museum.

At the same time, attention began to develop – and became almost pre-eminent in the second half of the 19th century – for a primitive phase of Brescian painting, and specifically for frescoes. The trend followed that of critical studies, and as the myth of the protagonists of the Renaissance was consolidated, precedents and ‘primitives’ began to be discovered, and numerous frescoes from churches and palaces, mostly anonymous 14th- and 15th-century ones, arrived at the Pinacoteca.

There is also a great moment of attention for Lattanzio Gambara, and an important moment for Vincenzo Foppa, whose historical and artistic identity as progenitor of the Brescian school had not yet been recognised. Then real waves of interest that see the collection gradually enriched.

In 1903, the collections of the two picture galleries merged into Palazzo Martinengo. What were the reasons and who were the supporters of this merger project?

Mainly it was a matter of optimising management costs, in the same terms as we would imagine today. It had probably become difficult for the municipality to sustain two locations with two such important collections, and besides, there was a whole series of parallel institutes – from the Ateno di Scienze Lettere ed Arti to the nascent Museo del Risorgimento – that were looking for their own location. In some ways it was therefore a true process of optimising and systemising a situation that was complex and in some ways confused.

It was also a moment of great impetus for the city’s modernisation. In 1904, for example, the first great ‘Esposizione Bresciana’ of arts, trades and industry was organised, very ambitious and with a great deployment of means, marking the conclusion of a phase – marked by the political leadership of Giuseppe Zanardelli – which for Brescia was one of great development and a yearning for modernisation on all fronts, beginning with industry and extending to town planning and the cultural system.

In this respect, the decision to merge the two picture galleries was not only to reorganise the venues, but also to rethink the collection, so much so that the first real director of this newly-born picture gallery, which brought together the two previous souls, was for the first time not a painter, as had been the case until then, but an art historian, hence a scholar, an expression of this ambition towards modernisation.

Once completed, the Pinacoteca was opened to the public in 1914, with a new attribution to Raphael and after a programme of acquisitions in the areas of the Brescian Renaissance, the 17th century, but above all the 18th century, which had not yet been comprehensively re-evaluated. What role did Giulio Zappa play in the reorganisation of the museum?

It was Giulio Zappa, a pupil of Adolfo Venturi, who was the first art historian to be appointed director of the Art Gallery in 1911, when there were still very few graduates in this discipline in Italy. His task was precisely to rethink this nucleus that had been created with the merger of the two historical picture galleries, and to give it an order that was no longer that given by the arrangement of the works according to criteria of size and compatibility from an aesthetic point of view, but one that was scientific in nature.

Giulio Zappa created a chronological route and within it a distribution by schools, which among other things allowed him to identify gaps in the collection. His programme does not envisage a simple reorganisation of the spaces, but rather a redefinition of the museum in an organic way. In this regard, Zappa is concerned, for example, with subscriptions to international journals, the purchase of books, and correspondence with other scholars. It is from this impetus that two of the most important acquisitions – the Merchants’ Altarpiece by Vincenzo Foppa and the Laundress by Giacomo Ceruti – and the rediscovery of the Angel as a work by Raphael were born, moments that did not end in themselves, but gave rise to a new direction in the history of the museum, a direction that still characterises the Art Gallery today.

Recognition of the Angel as a fragment of Raphael’s Coronation of St. Nicholas of Tolentino altarpiece is due precisely to Zappa’s contacts with the German art historian Oskar Fischel, and his ability to welcome and house it, but also to support the long research path – which passes through painstaking restoration work – that brings the work’s authorship back to Raphael.

The other important element is certainly Vincenzo Foppa’s openness towards an artist who was practically being discovered at that time, but also the welcome given to Giacomo Ceruti: when Zappa chose the Laundress from among hundreds of works offered as a gift by a collector from the province of Brescia, that was the first work by the artist to enter a museum in Italy under the name Giacomo Ceruti, of whom there was evidently a local memory, although the artist had been completely forgotten in the literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It is from this acquisition that the entire reconstruction of Ceruti’s corpus begins, so it is Zappa’s ability to keep up to date, and probably also to perceive the importance of certain developments in art history, that leads him to make choices that remain cornerstones in the physiognomy of our museum. Giulio Zappa’s story is moreover one with a very sad epilogue: he died in an Austrian prison camp in 1917, and from the front he wrote heartbreaking postcards in which he asked for news of ‘his’ art gallery. He was a character who, in a very short space of time, gave the museum a decisive turnaround.

After the Second World War, a new season began for the Pinacoteca. A generation of young critics and the expansion of studies around Brescian painting, encouraged by the 1953 exhibition on The Painters of Reality in Lombardy curated by Roberto Longhi, gave rise to an interesting programme of acquisitions from the 1960s onwards. Which decisive works enriched the Pinacoteca?

This was the moment when the people of Brescia realised that they had a local painting tradition that was not only worthy of being remembered, but also characteristic and characterised. If up until then they had reasoned in terms of local glories, thanks to Roberto Longhi there was a growing awareness of the importance and specificity of Brescian artists in the history of Italian painting, which was reflected not only in the Pinacoteca, but also in the city’s collecting policies, which until then had rather disdained local painters.

In the Art Gallery, this turning point was marked in 1963 by the first real acquisition of a work on the antiquarian market, Romanino’s Saint Jerome, which initiated a real programme of acquisitions that until then had been limited to the transfer of works from churches or public institutions that were selling their property. This is also reflected in the organisation of the exhibition itinerary, in which Brescian painting decidedly takes the upper hand, to the point that in some stagings Raphael is almost presented as a ‘di cui’ of the Tosio collection. This phenomenon especially concerns Ceruti, who is the painter of the Brescian tradition that has grown most in the Pinacoteca’s collections over the years, and of whom Longhi is one of the standard bearers.

After major renovation and restoration work on the palace, the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo reopened in 2018 with a new exhibition itinerary. What are the themes underpinning the current museological project?

The current project is rooted precisely in the awareness of this story that I have told you, insofar as, as it was for Giulio Zappa, the most demanding challenge for us today is precisely that of reconciling two nuclei that originated with completely different intentions and in completely different ways: the collecting one with Tosio and its surroundings, and the Brescian one. We have created an interweaving that runs along a chronological path and can be perceived and read at various levels. The history of collecting is an important level for us, which emerges karstically in the story we tell about the Art Gallery.

When we set our objectives and the concept for this museum, we wanted to create a balance between these two souls, because over time one had always prevailed over the other, and in order to restore legibility to the Tosio collection, we strongly wanted the 19th-century works, which had been removed from the permanent exhibition after the Second World War, to return to the Art Gallery. At the same time we also gave space to another strand of Brescian collecting, which was already in nuce included in the Tosio collection, namely the collection of objets d’art that had found in another Brescian collector, Camillo Brozzoni, a leading protagonist.

Another element that we strongly wished to emphasise is the international scope of this collection, expressed both by Tosio’s cosmopolitan vision and his collecting, which was born in an intellectual environment strongly marked in this sense; and by the first real admirers and discoverers of Brescian painting, who were not local, but were the great European connaisseurs of the 19th century; and finally by Camillo Brozzoni’s collecting vein. Hence the desire to reduce the number of works on display, as if by reasoning in terms of absolute masterpieces, rather than aiming for exhaustiveness. Even the velvets, which characterise the new exhibition design, are a choice in the tradition of European picture galleries.

In 2022 new acquisitions enriched the 18th century section built around the Brescian period of Giacomo Ceruti, the protagonist of this exhibition season celebrating Brescia as the Italian Capital of Culture. What links Ceruti to the Pinacoteca, and what new elements does the exhibition dedicated to him highlight?

Four years after its opening, we were fortunate enough to rethink a sequence of seven rooms dedicated to the 18th century, which, when the Pinacoteca opened in 2018, were in some ways the weak point of the layout. We were aware of this, but the physiognomy of our collection at the time did not allow for more.

When we imagined dedicating 2023 to Giacomo Ceruti, as an artist representative not only of the Pinacoteca and the local history of painting, but also of Brescian culture, we initiated a programme that is built around the temporary event of the exhibition, but is based on values that do not want to be ephemeral or destined to leave a memory only in a catalogue. Thus, the occasion of the exhibition gave rise to new acquisitions generated by donations, bequests and deposits, which in a short period of time brought eleven works from the 18th century, including four paintings by Giacomo Ceruti and others by artists dedicated to genre painting. This made it possible to completely rethink the section, redistributing the works and creating a much more organic narrative, in which Ceruti is told from different points of view, and it is precisely this multiplicity of perspectives that is the strong characteristic of the exhibition. The commission to David LaChapelle of the work Gated Community, inspired by Ceruti and the theme of poverty, is also an initiative designed to leave a concrete outcome in our collections.

The reasons that led us to choose Ceruti as the protagonist of this 2023 are numerous: because the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo is Giacomo Ceruti’s museum, where the largest number of the artist’s works in the world are conserved; because his rediscovery begins here with the entry of the Laundress; because Giacomo Ceruti is an artist that, though Milanese by origin, the people of Brescia feel as a fellow citizen; because our city is the place where his memory is cultivated, is maintained, and has been maintained in the past, where he made his debut and left the most original part of his production, the part that is also the most famous.

When we thought up the exhibition, we believed that first of all Ceruti’s attention to the humble should be recounted – as was done in the famous monographic exhibition that Brescia organised in 1987 – because this has been a distinctive trait of Brescian sensitivity and culture since time immemorial: already in the 15th century, Brescians organised hospitals, pious places, confraternities dedicated to assistance, and even today ours is a city that has a great capacity for hospitality, which it also demonstrated in the face of the pandemic.

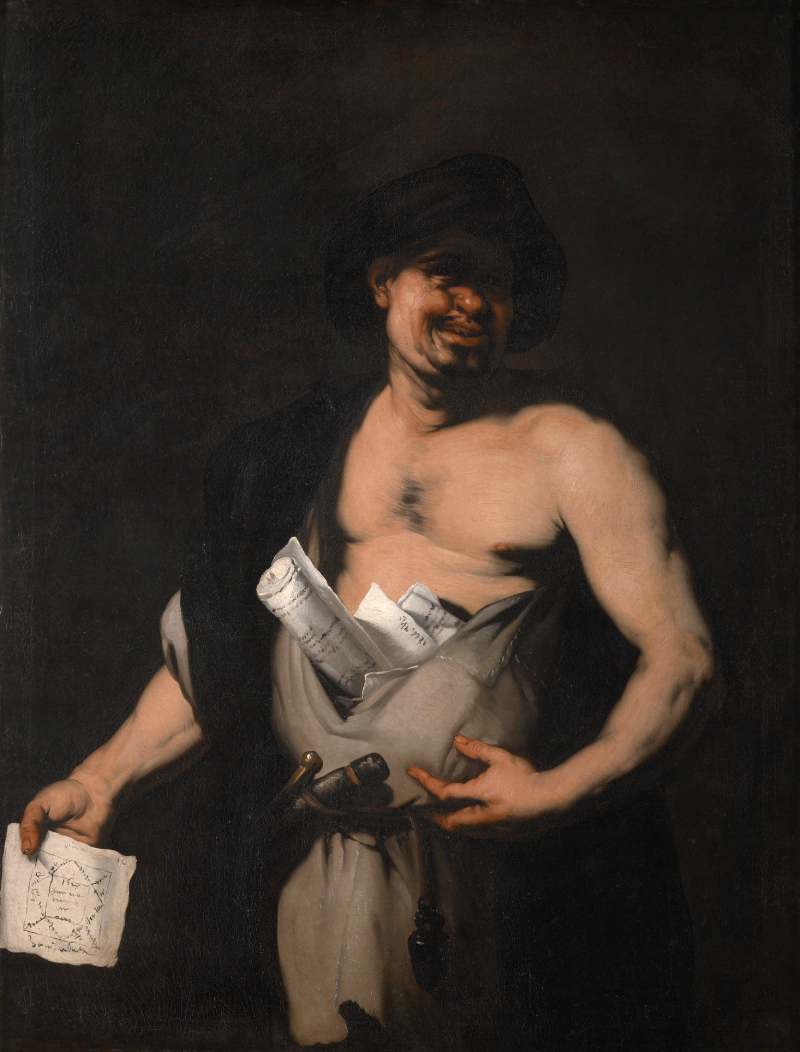

But the pauperistic trait of Ceruti’s painting was nothing new. We also wanted to show the other sides of this artist, who frequented many genres throughout his life, sometimes daring, sometimes leaving us works of discontinuous quality. And this passing through different registers always took place on a European dimension, never a local one: not only do the paintings of the poor have their most appropriate counterparts in the work of great European painters, but even when confronted with genres that are perhaps less akin to us today, such as the head of character or the costume scene, Ceruti is a European painter. In order to emphasise this dimension that goes far beyond the local dimension, we did not want a strictly monographic exhibition as was the case in 1987 but intended to build moments of dialogue and comparison between Ceruti and Italian and European artists preceding and contemporary to him along the exhibition route.