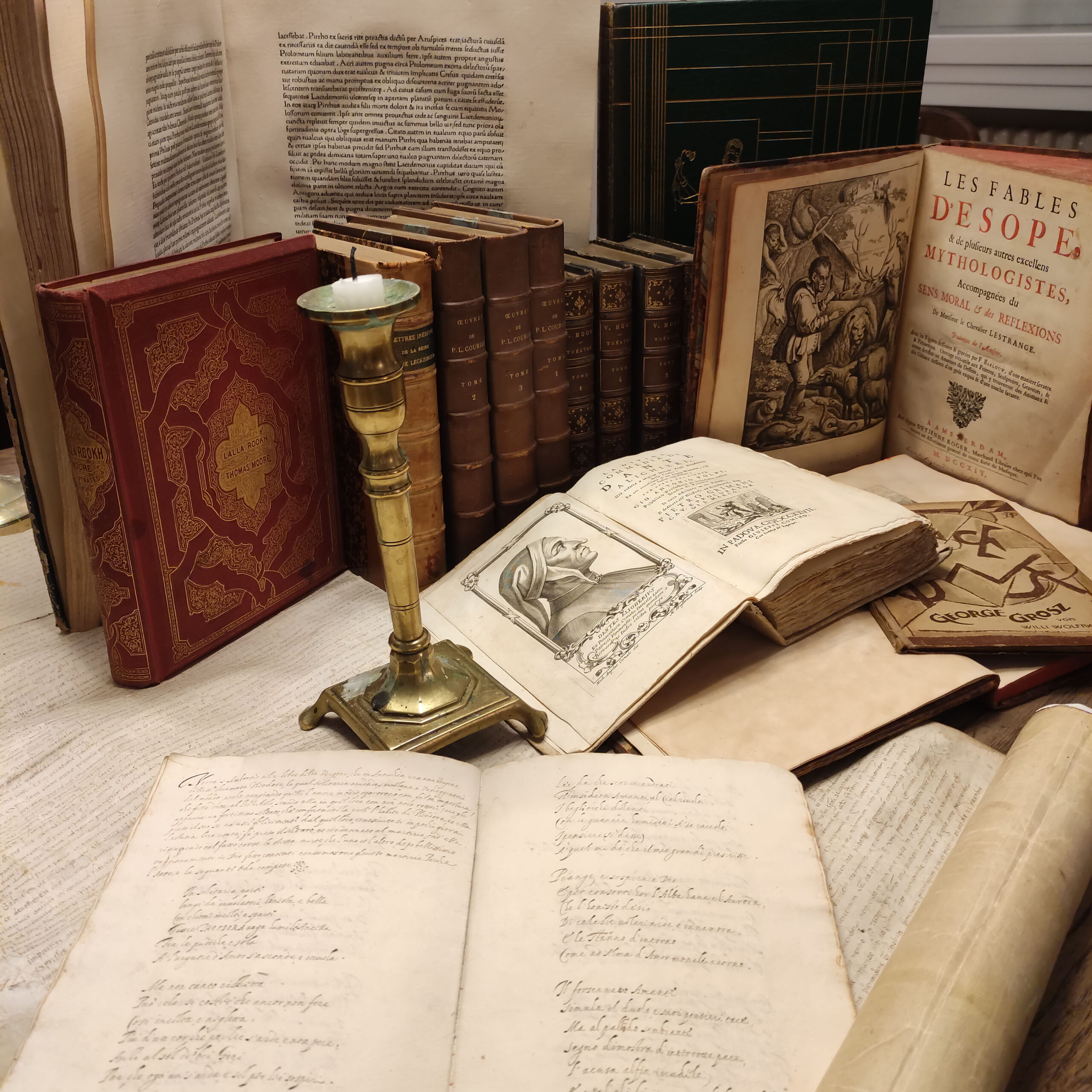

Exibart’s Erica Roccella interviewed Riccardo Crippa, head of the new Books and Manuscripts department, who will present his first catalogue on 18 May in the Milan premises of Palazzo Recalcati. Reading this conversation on the market and collecting antique and d’artistes’ books brings to mind a phrase by the Japanese writer Haruki Murakami about the physical pleasure of owning a volume: “I used to read and reread the same book many times, and sometimes I would close my eyes and fill my lungs with its smell. Simply smelling that book, running my fingers through the pages, for me was happiness‘.

Let’s start at the beginning. How did your passion for antique books and manuscripts start?

My first ‘encounter’ with antique books came about at the age of 12 when I fell in love with a copy of Carlo Botta’s Storia d’Italia from the beginning of the 19th century with a beautiful red binding that I found on a stall and that my father, quite amazed, decided to give me as a present. Since then it has been a crescendo. I remember when, at the age of 15, I told my parents that I had invested practically all the money I had saved between Christmas and birthdays in an illustrated Orlando Furioso from the 1500s: they looked at me like one looks at a madman. I sometimes think back to those moments and that sense of magic that every hard-earned purchase brought with it, for a provincial kid to have tangible signs of past worlds in his hands was to be able to be part of them and escape from reality. Perhaps my father had a point about my madness after all.

And then, how did it go on?

It was during my first year at Bocconi University that I started working as a file clerk at a Milanese auction house where I met my first teacher. Having learned the rudiments, I spent the following summers in London, first at Christie’s and then at some important bookshops – important experiences that gave me a deeper understanding of the industry and how it works. Putting my passion aside for two years, I graduated in Strategic Management in Rotterdam and started my career as an insurance broker in the Fine Art and HNWI field. Feeling that what I had embarked on was not my path, I did a few interviews and in the meantime decided to take a short break and embark on a ‘peculiar’ car race, the Mongol Rally, with destination Ulan Bator. It was in Uzbekistan, busy changing yet another flat tyre, that the news reached me that I would be re-entering the world of antique books as a specialist for a Milanese auction house. And after another four years in the company of books, thanks to the trust of Guido Wannenes and Luca Melegati, here I am now opening and heading a new dedicated department. I would like to meet the 12-year-old boy today who was looking all proudly at his red binding and marvel with him at what came from that stall.

How do you imagine your typical day at Wannenes from now on?The classic of every auction house professional: never one day is the same as another. It can happen that you receive phone calls from nice old ladies who think their encyclopaedia is worth a fortune as well as absent-mindedly answering while on a train and being offered a Nuremberg Chronicle (NB Schedel Hartmann, Liber Chronicarum. Nuremberg: Koberger, 1493). It happens that the sale of an important piece goes quietly and smoothly with just a few e-mail exchanges, while the study and sale of a small lot turns into a nightmare. The only real constant is an analytical approach to book valuation and attention to each work submitted, regardless of its apparent value. In fact, in a world as vast as the world of books, one must always be humble and limit the influence of one’s preconceptions because what may seem to be a somewhat battered little book may turn out to be a small treasure.

In general, how healthy is the book market – also in light of the year just ended?

The market as a whole is healthy and from the air one breathes at auctions and fairs I would say that, like other categories of collectibles, there is now more and more polarisation: the historically and artistically very relevant or extremely rare pieces have great fortune, the medium is faltering and there are large exchanges, especially online, of minor and curious works. There are the occasional lucky fads that make an appearance and last for a few years and some macro categories (such as medicine and architecture) that face a momentary slow decline. Since it is such a vast and varied world, it is impossible to give indicative numbers, but my opinion is that, to paraphrase the famous passage from Il Gattopardo (of which I happened to sell the first edition, by the way) everything seems to change in a world that remains always the same, i.e. the micro-dynamics, fashions and technicalities change, but the forces that move this small market are not very different from those that animated it a century ago.

Is it daring to consider even rare books as safekeeping goods, in the same way as works of art, diamonds and luxury items?

The book market is a traditional market and tends to be stable when analysed over the long term. I looked at this for my thesis and basically, although partial, the results confirm an alignment for the past years with inflation. It is certainly not the ground for great speculation, but it can be considered a safe haven asset like other categories of art assets. However, since it is a very vast field and impossible to index, to navigate well within it from an investment perspective one must necessarily either develop an excellent independent understanding of the market over the years or rely on trusted professionals, auction houses or bookshops. What I always stress, however, is that bibliophilia must first and foremost be a passion, a passion that, it must be said, has also infected important businessmen and economists, from Jp Morgan to Keynes.

Any recent adjudications you have followed with interest, around the globe?

I follow with interest the sale of NFTs related to early internet experiments, such as the sale of the first tweet a few years ago for $2.9 million. My opinion is that this is a field very much related to the traditional book and manuscript market. After all, these are important evidences of the evolution of written communication and it is already possible to find at international auctions, alongside parchment-bound tomes, important examples of PCs, typewriters and the like. Tomorrow’s collector will have the first tweet in his wallet and a papyrus fragment of the Iliad (a clipping slightly larger than a business card was sold by Aguttes in November for €35,000) and a page of the Gutenberg Bible (which can be bought for between €50,000 and €100,000) to keep him company.

Let’s talk about targets. Books are a very broad sector, ranging from manuscripts to artist’s books, to more contemporary experiments. What kind of collectors do you expect in the Wannenes parterre?

The thing I appreciate most about this field is that it is almost limitless. To date, I believe I have compiled and contributed to over 7000 cards between single books and multiple lots, and my eyes will certainly have rested on almost a million cards and volumes. Every day I get to examine material I have never seen before. From such a varied source I expect – and so far I have found – an equally varied collection that does not follow fashions and does not pretend to create them, but wants to be a pure expression of individual curiosity. There is nothing more satisfying for me than chatting with customers about their collections and passions and finding myself each time learning and hearing stories and anecdotes I have never encountered before. We therefore cover everything from incunabula to artists’ books and are also open to some experimentation.

Have the lot selections for the first auction already started? Have you already tracked down any curious specimens that you can anticipate?

We are still collecting material at the moment, but we can already anticipate that we will have a first edition of Poliziano’s opera omnia printed by Aldo Manuzio in 1498, an important Avicenna in a coeval binding on wooden boards printed by Lucantonio Giunta in 1520, an amusing collection of late 18th and early 19th century texts on oenology and gastronomy, a collection of beautiful illustrated texts from the 18th century, and a few important surprises still being catalogued.

The most valuable book you have ever leafed through?

I have come into contact with many masterpieces, and excluding books I have perused in libraries or institutions, I recall having “collated” (i.e. checked for all pages and plates) in London a First Folio, the first edition of all Shakespeare’s works printed in 1623 whose last copy sold at auction at Sotheby’s in 2022 for $2,470,000 (Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies. London: Iaggard, Bound 1623). Other valuable books in economic terms and in terms of importance that I recall with pleasure are the large and famous bird’s eye map of Venice Venetia MD by Jacopo de Barberi (Venice, 1500), Luca Pacioli’s valuable Summa de arithmetica (Venice: Paganino de Paganini, 1494), the first edition, printed in only one hundred copies, of Manzoni’s first work, In morte di Carlo Imbonati (Paris: Didot 1807), and Depero’s Il modernissimo Bullonato (Rovereto: Dinamo Mercurio, 1927).

The book you dream of seeing pass under Wannenes’ hammer, however?

In purely economic terms, I wouldn’t mind at all a nice Gutenberg bible, perhaps annotated by the Master and coming from the library of Frederick III of Habsburg. The reality, however, is that this job makes you learn to love too many things and my current wish list would be too long to be published in this article. I am sure, however, that in the coming years I will see unique lots pass under the hammer, a world made up of ancient and modern fascinations that tell us the history and passions of mankind and that survive us between passages at auction and centuries spent undisturbed on the shelves.