The automobile is a very specific design theme, which is articulated vertically. With the exhibition ‘DNA. I geni dell’Automobile nell’industrial design’, realised together with the ADI – Compasso d’Oro museum in Milan, running until 26 February 2023 in the two exhibition venues, we want precisely to bring into dialogue, and even better to create a bridge, between two worlds – that of industrial design and that of car design – which have separated over time. We note, in fact, that while the Compasso d’Oro, founded in 1954, initially also awarded cars – for example the FIAT 500 in 1959 – it then had twenty-five years of silence. Only recently has this custom been revived, such as the New Panda in 2004, and the Ferrari Monza SP1 in 2020. The fact remains that while car design remains mainly linked to Turin – even if Milan also has its own tradition of special bodywork – design tout court, in a broader sense, has its centre of reference in Milan: two worlds that talk to each other and look at each other from a distance. In reality, we must also emphasise that the car is a highly evolved expression of design, certainly more complex than a piece of furniture, be it a table, a chair, a light fixture, because it has a very articulated technological research. To this must be added the evocative power of experience, of the load of suggestions, and of the memory that a car carries when it is historic. It is therefore a social fact, as well as a symbol of freedom linked to the pleasure of travel and escape. And then there is the motoring and emotional aspect of great speed, of the expression of power, which leads us to look forward to technological development. These are all characteristics that only the car and no other design object embodies.

Today the car is going through a difficult phase: we are moving to electric propulsion, and slowly to autonomous driving, and we still don’t really know what the car of the future will look like, we only have hunches. On top of that, by some it is viewed with hostility, with antipathy, it creates tension because it is associated with something harmful and useless, and this extraordinary charge, this historical path made by the automobile, which grew with Futurism and then became more and more stable, solid, in some ways technically exciting, is now going through a problematic season.

Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, Maserati, and the Pista500 at the Lingotto in the shadow of Renzo Piano’s Scrigno, which houses the wonderful works of Gianni and Marella Agnelli collection. What do these projects have in common and what makes them unique?

As an architect, I have realised many projects for all kinds of buildings, such as public services, commercial, offices, churches, hospitals, spaces for sport and culture, but my most personal field remains architecture for the automobile. For Alfa Romeo, in 2015, I entirely rethought the architecture and design of the layout of the Arese museum – the historic building of the Latis brothers had been abandoned for years and no longer met contemporary criteria -, preceded, between 2001 and 2003, by the idea of the Alfa Romeo Gallery in Milan at the Bicocca and numerous stands in Europe; also for Maserati, I created stands in eight different countries around the world between 2014 and 2016; and for Ferrari, I designed the two Ateliers and the Hospitality in 2011-2012, and the layout of the Ferrari Museum in 2018. And then La Pista500 in 2021, which transformed the historic test track on the roof of the Lingotto into a large sustainable garden, a project that is architecturally different from the others, but united in the technical, historical and cultural knowledge that I have assimilated over time of these glorious automotive brands. All this stems from the fact that I grew up with a father who was advertising and communication director for Fiat and then Fiat Auto for over thirty years, and even as a young boy I saw projects for launches, presentations, car showrooms. I have absorbed a lot of this culture of the relationship between a brand and its exhibition expression, and how this is then declined in dedicated places and spaces. This knowledge I put into Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, Maserati, trying to fully interpret the meaning of these historic brands of the Italian car in the world, which are similar but different.

The Pista500 at the Lingotto is, as I said, a very different project that relates to the history of 20th century industrial architecture, because the Lingotto is perhaps the industrial architecture that most transcends being just industrial, both for the marvellous helicoidal ramps and for the track on the roof, designed by engineer Giacomo Matté Trucco, which have become true icons of architecture tout court of the last century. When the Lingotto was inaugurated in 1923, some photographic images and drawings went around the world: they were noticed by Le Corbusier, who published them in his art and architecture magazine ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, and the following year, in 1924, in the second edition of his collection of essays ‘Vers une architecture’, which theorised the new languages and forms of architecture, giving the Lingotto a value as an icon of the modern movement. This idea of the street running above the roofs of buildings was taken up by Le Corbusier with the Obus Plan for Algiers in the 1930s, which was never realised, but which somehow defined the poetics of elevated infrastructures: a concept that belongs to the modern that becomes extraordinary with the Lingotto. All this is to emphasise that designing a roof garden on a very important historical memory of the 20th century, celebrated by Le Corbusier, was a difficult task; the same Renzo Piano who redeveloped the entire Lingotto and placed the Bolla and the Scrigno on the roof, left the runway intact. Unused, except occasionally for a few small events, and having lost the function for which it had been created, the track had become an expanse of asphalt with no meaning other than that of its memory. From the Art Gallery, therefore, came the project to take up the idea of New York’s High Line, where the urban infrastructure – a disused section of the elevated railway – became a highly successful linear park. The historical value of the track led us to realise a very sophisticated, light project with large islands of basically autochthonous nature: 40 thousand plants of 300 different species from Piedmont and Liguria. The islands are like leaning along the track, which remains for the use of electric cars only, and give a feeling of lightness: a re-edition for the new millennium of the century of cement, of speed, of industrial power. Today we are different.

The Museo Nazionale dell’Automobile di Torino – the MAUTO – one of the oldest of its kind, listed by The Times as one of the 50 most beautiful museums in the world, was founded in 1933, the brainchild of Cesare Goria Gatti and Roberto Biscaretti di Ruffia, and today houses 250 models of cars from international brands. Between past and future, what makes this extraordinary collection alive and relevant?

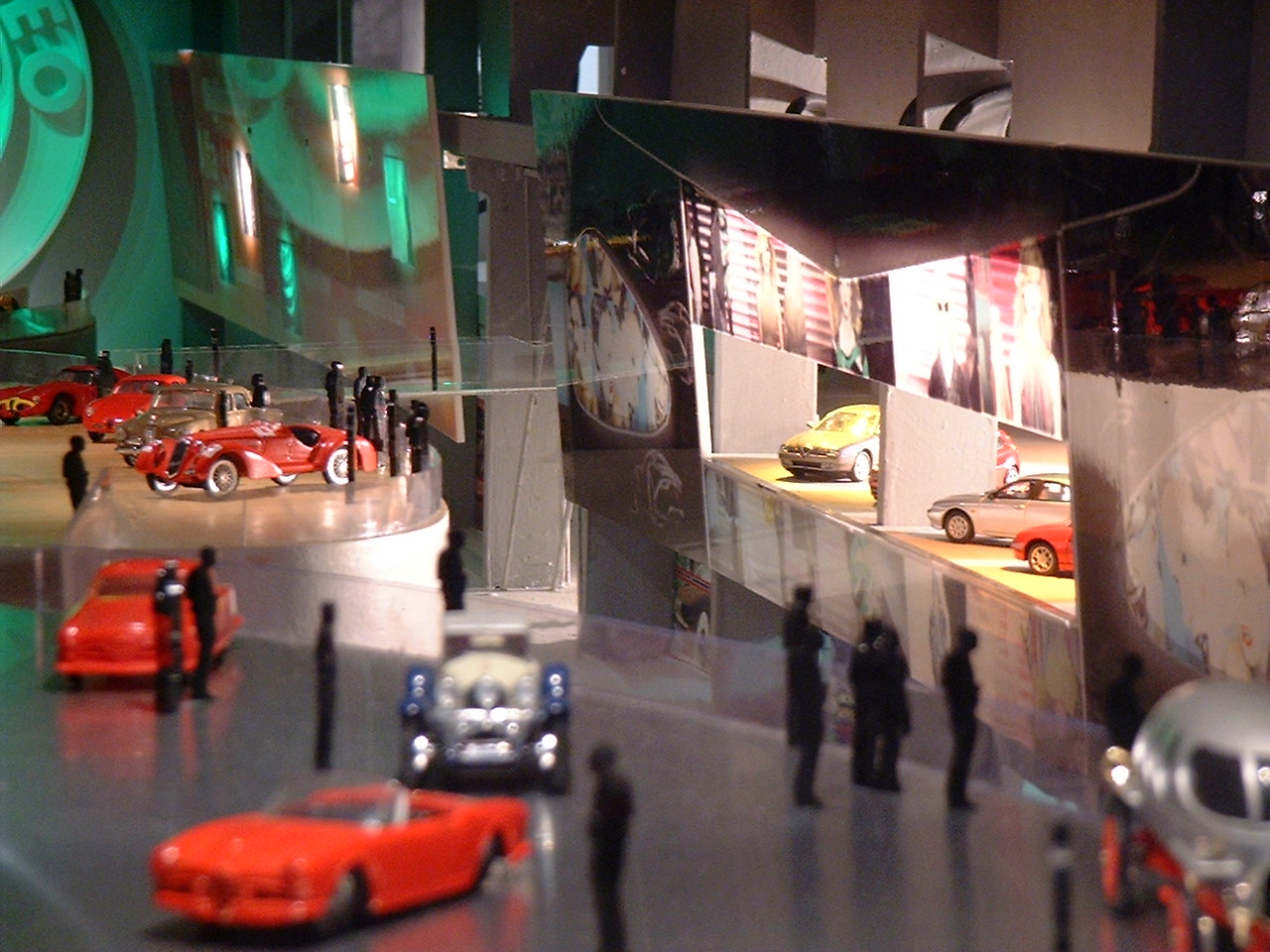

The MAUTO is the first museum in the world to be founded with the idea of celebrating the history of the automobile, apart from the museum of Compiègne in the Oise, dating back to 1927, which, however, only collects models of French national manufacturers. Already the year before its foundation, in 1932, Carlo Biscaretti and Cesare Goria Gatti laid the foundations of the museum with a retrospective in Milan of around 50 cars, which would later form the core of the collection. They were the first to come up with the idea and collected the most incredible and marvellous cars – almost all of them free of charge – up to 1959, when Carlo Biscaretti passed away. This gave the museum an unrivalled historical collection base: there is no other museum in the world that has such an extraordinary completeness of history and models, both in terms of industry and design. The MAUTO also includes the documentation centre with its archives and library; the restoration centre; a space dedicated to temporary exhibitions; and educational workshops. Returning to the museum’s history, with the commitment of Gianni Agnelli, a lawyer, and funds allocated by FIAT and several other companies, not only automotive, the collection finally found an exhibition venue in 1960, designed by architect Amedeo Albertini, who designed a formidable building with an international slant, anticipating in its conception the international museums of the 2000s, with spaces of great breadth and size. The building was further enlarged by architect Cino Zucchi, and reopened in 2011, after being closed for four years, on the occasion of the 150th Anniversary of the Unification of Italy, with a new layout designed by the Franco-Swiss set designer François Confino, conceived not only for specialists, but for everyone.

My arrival at MAUTO as president dates back to 2012, the year after its reopening, with Rodolfo Gaffino Rossi still as director, a true ‘metalworker’ with an intense professional career at Fiat Auto, who in sixteen years of commitment assembled and built this museum. After he left in 2018, he was succeeded by Mariella Mengozzi who, by virtue of her many managerial experiences within Ferrari and beyond, brought a new season aimed at communication and marketing of culture, to export this extraordinary museum to the world. Turin is a relatively small city, it is not Paris, London, or New York, and we suffer a little from this, so our present objective is to put the national museum at the centre of a European and even American system of knowledge of the culture of the automobile. Next year we will be 90 years old, which we will celebrate with an exhibition on the future of the automobile in awareness of an extraordinary past. We want to be, and we are, a very active museum, and there are several awards that we have received just this year that make us proud: the La Bella Macchina award at the Concorso Italiano, as part of the Monterey Car Week event in California; the Eccellenza 2022 award from ACI Storico; the Ruoteclassiche – Best Classic award as the best museum in Italy; and last but not least, the prestigious Heritage Cup from the FIA – Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile. So many projects in the next ten years, up to the centenary, growing as a stronghold in automotive culture.

Turin has always been the city of the automobile, which in over one hundred years has given birth to seventy car manufacturers and eighty coachbuilders. A unique heritage to which MAUTO bears witness. Can the memory of a glorious past be a bridge to a bright future for the automobile and the city?

Certainly it can, but it is not a certainty. If we look at the memory of the past, it is very structured: Turin is a great and true motown, as are Detroit and Paris, the great cities of the automobile, and to some extent also Stuttgart, Berlin and Munich. In a room of the museum called ‘Autorino’, we have staged a large aerial photograph on the floor, with the location of the 130 car manufacturers – coachbuilders or complete manufacturers – born and raised in Turin and almost all of them disappeared: an absolutely incredible number. And this very important history, this heritage of the city, can also be seen as you walk around Turin, in the historic buildings that still stand as testimony to this illustrious past, such as the first Fiat, Lancia, Diatto, and where the Lingotto symbolises the extreme tip of memory, of what the pioneering automobile industry was for the city. And how can all this be a bridge to the future? It is when these illustrious vestiges continue to be inhabited by engineers and where research continues, an attitude that is in the very DNA of the city, where the Savoys brought the tradition of military genius, promoted technological knowledge, advanced construction, and this predisposition to applied sciences remains very strong in Turin with the Politcnico, which has the structure and capabilities to dialogue with automotive companies. There is a strong osmosis between training, research and application, which is yielding very interesting results for what will be the car of the future: from design, to engineering, to the advance design that envisages and experiments with what will be the structures, the shapes of the self-driving car. Among other things, Turin has some truly authoritative business acceleration centres, such as OGR Tech and Intesa Sanpaolo’s Innovation Center, where research is developed that competes in every technological sector. Thus, Turin has a strong presence of the study applied to innovation, which in this phase, in this decade that we are living through, where exponential and extremely fast digital acceleration is constantly imprinting technology with innovation, can make Turin an industrial capital once again, a vocation that the city has partly lost in recent years.

In the art market, the car represents a safe investment, far removed from market fluctuations and passing trends, when uniqueness, state of preservation and provenance are present. A selection principle that unites the most iconic Ferrari or Bugatti with the must-haves of modern art. True luxury, is it the contamination of genres combined with the beauty of the work of art that makes it always contemporary with its era?

The automobile is not pure art, but there is undoubtedly a strong art component in its beauty. What is said among designers, in fact, is that what is ultimately remembered is always the form rather than the engine, which through intelligent and targeted marketing hits the emotional sphere of the public. It is the evolution of the form therefore that constitutes in some way an artistic expression, which brings some cars on the auction market to even very high valuations, such as the Mercedes 300 SLR Uhlenhaut Coupé from the 1950s, produced in two examples, which went on sale in May 2022 for 135 million euros, making it the most expensive car ever. There is, however, one important fact to underline: the art collector buys the work for himself, he may show it in the privacy of his home, he may lend it to an exhibition, or even keep it secret; the car collector, on the other hand, likes to show off, to be seen driving his car, to participate in the concours d’elegance of Villa d’Este, Pebble Beach, or Goodwood, to somehow enter an extraordinary elite of great collectors, sometimes even too ostentatious. In any case, it represents status, whether it is a work of art or a car, and collecting one is not independent of the other.

When you founded Camerana&Partners in 1997, your ambition was to realise projects that interplay architecture and landscape in full respect of environmental protection and energy saving. Twenty-five years later, in the 21st century, do you think you have achieved these goals, and what are your next visions?

Green architecture, which brings nature into architecture as material, as function, as presence, has characterised my studies and research. My manifesto was still the Environment Park in the 1990s, which redeveloped a disused area of heavy industry in Turin into a complex of research laboratories with the roofs transformed into a public garden, a park, and completely renewable energy sources; Therefore a total sustainable architecture project, on which I worked with the consultancy of Emilio Ambasz, an Argentinean architect trained in the United States and a person of great intelligence, as well as curator for many years in the architecture department of the MoMA in New York, whom we can consider the true promoter and propeller of green architecture, and of whom I feel culturally a son.

The Pista500 is the latest project that carries the same message of sustainability, albeit more refined and sophisticated in its relationship with history. What has changed from those 1990s to today is perception. The theme of sustainable architecture has exploded, it has become necessary and fundamental, and what we attempted as pioneers has now become the verb. At the time there was no lack of disbelief towards our project, thinking that somehow all this nature had to become ruinous for the buildings. Today architecture must bring greenery back into the city, but also look beyond it, have an extra vision, think, for example, of water as a presence in the structure of the city, as a building material; think of how to convert the use of cement, aware of the risk of devastation that this material brings to the planet; think of how to reduce energy and land consumption. There is a revolution to be carried out first of all in the world of construction, and we architects must be the leaders, giving signals, examples, strong messages that are a guide, so that the industry, laws, rules will adapt and lead the building industry to build with sustainable materials and less waste of energy.

This is the urgency of the present. Then, there is a fairly imminent vision of the future, which is space, because it is clear that in 15-20 years’ time easily accessible and habitable settlements will be brought and built on the Moon. This is my new and pre-eminent direction: we recently won the call for tenders for the feasibility project of the Grottaglie-Taranto spaceport, from where the first suborbital flights will start as early as 2023; we are working on the project for the Space Centre in Turin, a museum of space, culture, and scientific research; and with a leading player in the space industry that I cannot mention, we are thinking about how to perfect the interior design for the lunar spacecraft and space stations. The Moon is now our other planet. ‘Earth-Moon: Double Planet’ is a concept that has become a mantra: to work, to bring research, experimentation, production to the Moon, as a plan to save our planet.